This article was originally published by the Nonsense Newsletter team. You can find the original article here.

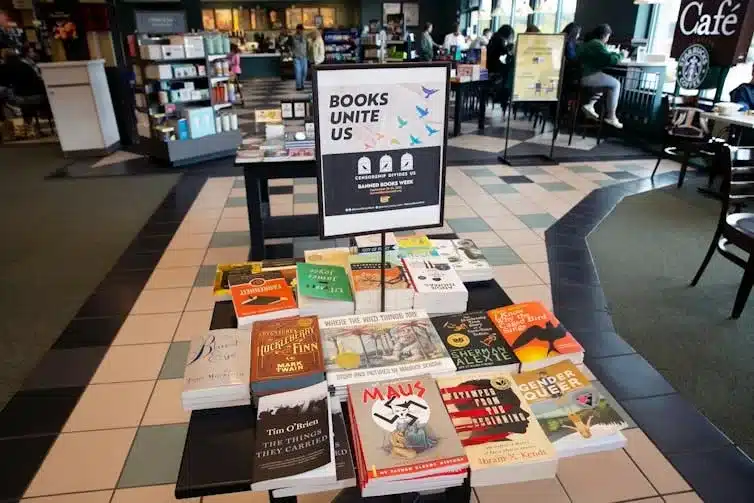

Gender Queer, a graphic-novel memoir of coming out as non-binary, was at the centre of Australia’s perhaps highest-profile book banning furore in recent years – that is, before western Sydney’s Cumberland City Council banned books on same-sex parenting.

And Gender Queer’s status is still threatened: Bernard Gaynor, the conservative Catholic activist who led the call to ban it is taking the Minister for Communication and the Australian Classification Review Board to the Federal Court of Australia. The decision will come later this year.

Researcher Nicole Moore told The Book Show’s Sarah L’Estrange recently that, contrary to what many of us think, this wave of book bannings is not copied from the US.

Australia has a long history of book banning and before Gough Whitlam’s government in the 1970s, was “one of the most censorious countries in the English-speaking world”. For example, in 1932, Aldous Huxley’s A Brave New World (now a standard school text) was banned in Australia.

“We have a long history of Christian associations and churches organising to ban books,” Moore said, particularly citing sex, sexuality and gender as reasons. The Gender Queer ban, she said, provoked “concerns about some models of Christian understanding that are perhaps narrow in their models of how people should live and how books should express the ideas of gender identity and sexual expression”.

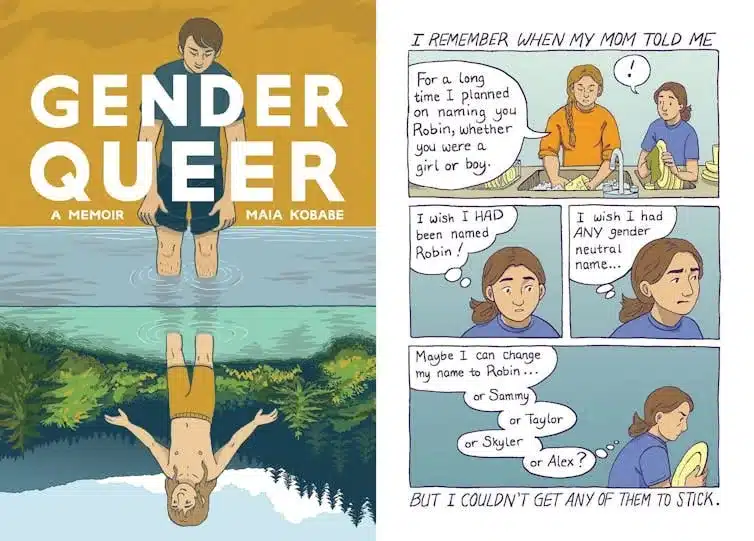

Sexually explicit illustrations, including of a sexual fantasy inspired by Plato’s symposium, are often cited (and taken out of context) by those looking to ban the book. But American author Maia Kobabe (who uses e/em/eir pronouns) told The Book Show that’s not why the book is so embattled. Rather, it’s the title, its comic form, its several major literary awards and that it’s a “happy” coming-out story “where I face no negative consequences from coming out”.

The book – which began life as “a well-received but minor debut book from a new author” – has become a story of censorship, culture wars, and of the way young trans lives have been caught up in ideology wars.

A journey towards awakening

In the US, Gender Queer has been the nation’s most challenged book for the last three years in a row. Initially published and marketed to adult readers, in 2020, it won the Alex award, given by the Young Adult Library Services Association to ten books written for adults that have special appeal to young adults. This led to the book selling out its next three print runs.

It’s the story of Maia Kobabe. Maia likes snakes, running barefoot in the fields, and playing with eir best friend Galen. Maia’s parents are both long-haired folksy types, who enjoy nature, crafts, hiking and music. In Maia’s early life, girls and boys aren’t radically differentiated from each other. When the best friends start attending school in grade one, Maia and Galen are delineated, separated by gender. Boys play in treehouses, girls have cooties. At school, Maia is inducted into a world where everyone seems to be in on secret information about girlhood.

Maia is aware from a young age that e doesn’t feel like a girl. But e doesn’t feel like a boy either. Maia recounts the trauma experienced in each gendered milestone like first period, first bra and first pap-smear. Kobabe also depicts Maia’s journey towards sexual awakening, exploring masturbation and first sexual encounters while also navigating a body that doesn’t fit the normative “penis in vagina” narrative in sex-ed classes.

Eventually Maia comes to acquire a language to describe eir gender identity as non-binary, including the Spivak pronouns e now uses.

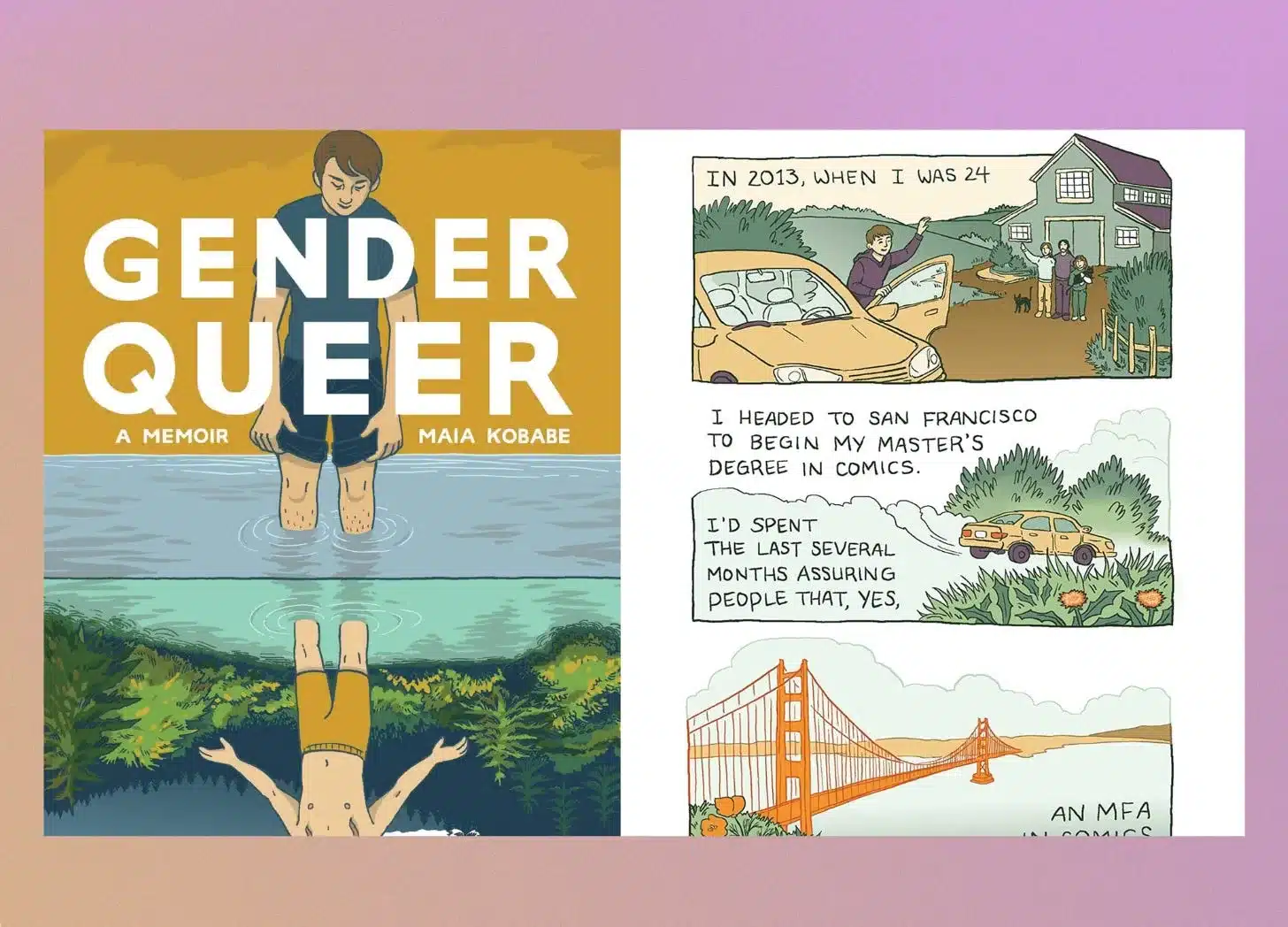

Like others before em, Kobabe realised ey could use comics as a medium of self-expression to convey this journey of identity. Comics can represent embodied experiences by bringing “insides” into contact with “outsides”. Thoughts and sensations are made manifest on the page. Comics can also show the way various social and cultural forces take root in the body. Kobabe began publishing eir comics on Instagram. The feedback was, says Kobabe, “immediate and so positive and so generous and warm and supportive”.

Australia and Gender Queer

In March 2023, Gaynor lodged an official complaint with the Queensland Police about Gender Queer and four other titles at Logan City Council’s library. He claimed the books breached the criminal code in relation to child exploitation material and exposing children to sexually explicit material. The police referred the matter to the Department of Communications and Arts.

Sydney bookstore Kinokuniya received an email from the Australian Classification Board calling in Gender Queer for classification. The bookstore faced three options: ask the international publisher to submit the book for classification, remove the book from sale, or classify the book themselves at a cost of $560. Kinokuniya chose to classify the book themselves.

In April, Kinokuniya received the Classification Certificate, stating that Gender Queer can be sold unrestricted, with a recommendation of M for mature readers (not recommended for readers under 15 years).

In May 2023, the decision by the Classification Board to allow Gender Queer: A Memoir to be sold unrestricted was appealed and a review of this decision was announced. The board received more than 500 submissions from the public. In July, the Classification Review Board upheld the original decision by the Classification Board.

Young adult writer Lydia Schofield notes an alarming trend of low-key censorship in Australia, where books quietly disappear from bookshops or libraries, without an official ban in place. She likens the practice to “shadowbanning” on social media, in which content is concealed or deprioritised by algorithms.

The Logan library service took Gender Queer off the shelf, so it would only be available to those who asked for it.

Gender Queer may have disappeared off Australian shelves altogether if Kinokuniya hadn’t paid the classification fee. Schofield points out quiet censorship can occur pre-publication, where publishers in a small market like Australia might not feel emboldened to take risks.

Early days

In 2019, Gender Queer was picked up by Lion Forge Comics (Lion Forge has since merged with Oni Press). Lion Forge’s yound adult imprint, Roar, had previously published Lighter Than My Shadow, a young adult graphic memoir about a young woman experiencing eating disorder recovery. Gender Queer was not published by Roar, but published for and marketed to an adult audience. Lion Forge released a relatively small print run for the US market of 5,000 comics.

Kobabe also writes about eir early experiences of publication in The Nib, remembering the support librarians gave the book in those early days. Kobabe recalls many librarians saying “I know exactly who I want to give this to”.

After Gender Queer won the Alex Award, a video of a parent railing against Gender Queer in a school board meeting in Fairfax, Virginia went viral in 2021. This sparked a series of copycat challenges. From July 2021 to December 2022, the book was banned in 56 school districts.

PEN America claims “where Gender Queer was read in full, rather than challenged based on a few illustrations with sexual content, many districts and school boards across the country decided to keep the book”.

Five of the ten most challenged books in each of the last three years featured LGBTQIA+ content.

A community impact

It’s difficult to estimate how many trans and non-binary young adults there are in Australia. In 2022, the ABC reported there were just 10 referrals to Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital for gender services in 2011. In 2020, that number was just under 500. In 2021 it was over 800.

In an afterword to the new edition, Kobabe writes,

Many of these pages hold things which at one time seemed like my deepest, darkest secrets, until I brought them out into the light and I realised they are just aspects of being human. The process of writing this book helped me figure out who I am. It also made me realise I am part of a wide community, all wrestling with the same questions.

It’s true that seeing ourselves reflected in literature might make us feel less alone. Other people’s stories help us find a shape and form for telling our own stories.

To me, the aesthetic appeal of Gender Queer lies not in the material details of Kobabe’s personal journey. Instead it is the reverberation between the dynamic figures at play inside and outside the text. Kobabe, the author, gazing benevolently down at her younger self. Maia, Kobabe’s character, gradually realising eir needs can only be met through the imperfect, hope-fueled art of authentic communication. Me the reader, and my own stories of periods, bras, pap-smears, body hair, masturbation, and feeling betrayed by my body.

And sitting outside this frame, the imagined young adult reader who might be the ghost of Maia Kobabe emself, seeing eir experiences mirrored for the very first time in the pages of a book.

—

Article from Penni Russon, Senior Lecturer, School of Communication, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.